Scroll down for update related to #OccupyChicago

Scroll down for update related to #OccupyChicagoSeveral years ago I saw Chicago: City of the Century, on a Washington, DC area PBS station. What is amazing about this documentary, like many others, is that it blatantly destroys fallacies of the Left without a single cry from a Leftist.

|

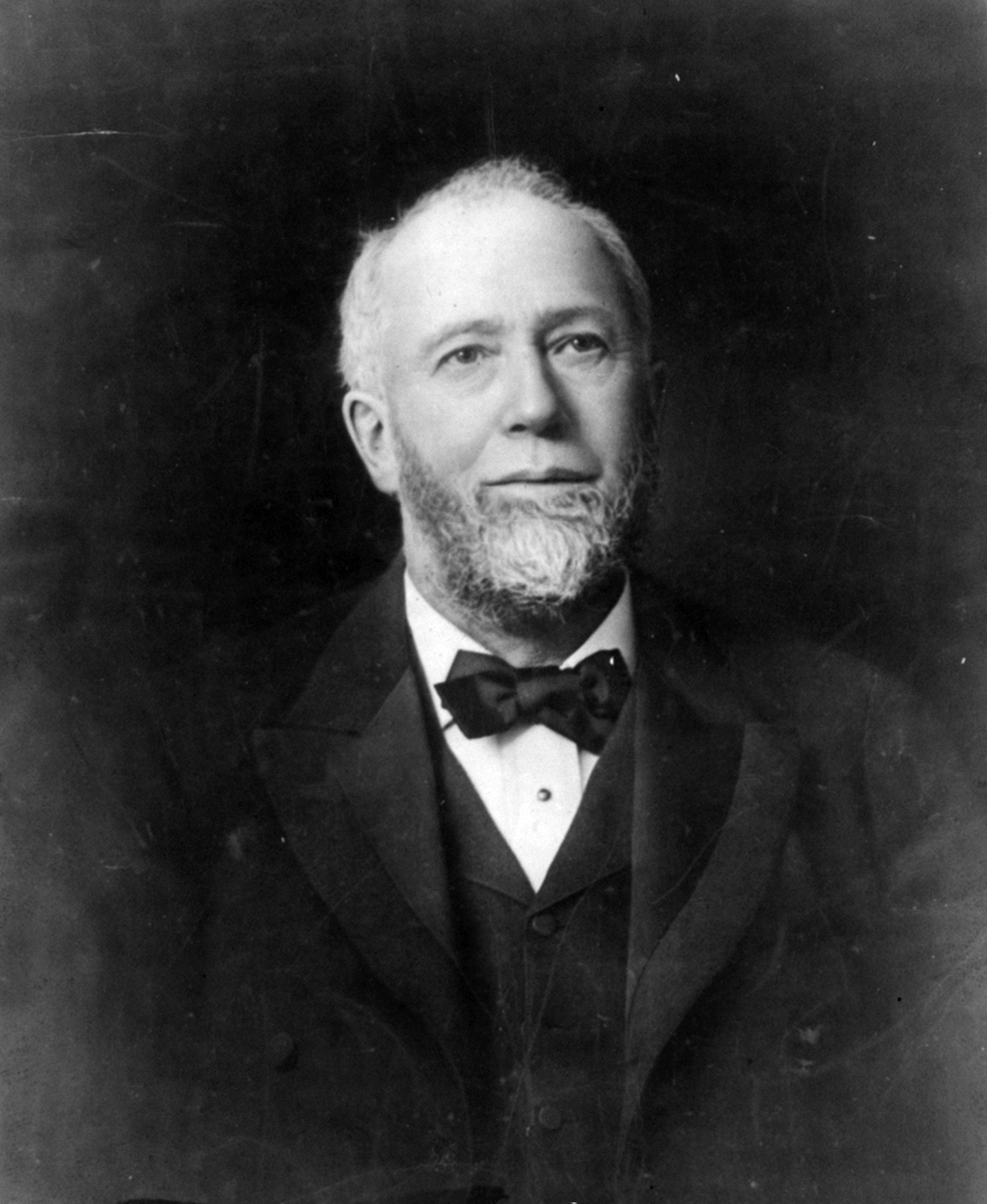

| Gustavus Swift |

Swift: Gustavus Swift would walk out to Bubbly Creek, which was this terrible little sewer that ran out of one of his plants, with his top hat, his dark suit, he'd have his pants tucked into his Wellington boots, and he would wade into Bubbly Creek to check what was coming out of the sewer. And if he saw any grease or fat then he knew that was waste because you could have turned that into lard. And he'd go back and he'd find the source of how that happened and correct it. He was a very hands on manager.Get that? No government agency was poking around looking for "pollution." The 'evil capitalist' owner was looking for sources of waste and eliminating them. How could the editorial staff of Slate and The Nation miss that one? Probably because they want federal money squandered on PBS and they do not bother witnessing what is escaping from Room 101.

Nancy Koehn, Historian: You can't understand industrial capitalism without understanding the importance of pennies, half cents, a tenth of a cent, a hundredth of a cent. And when you think about millions of pounds of beef being processed through a single plant in a year, you begin to understand why a hundredth of a cent was something that kept Swift and Armour and other industrialists up at night.

Part 2 continues and makes quite a few of the expected Leftist mistakes that one would expect from PBS. Like how railroads had cut wages by 40 percent. They actually mention this happened just after the end of US slavery, but fail to connect the dots. Two dots really, new labor flood begets lower wages.

This is also the part that covers the rise of Socialism in the USA, in 1877, with the Bohemian pied pipers from what is now the Czech Republic. (Just 23 years later, Yellow Socialism, aka, National Socialism, would emerge from the same area). It mentions how members left the Socialist Labor Party and joined the International Working People's Association. Without any fanfare, PBS casually mentions that the IWPA is an "Anarchist" organization, without noting that the big difference between the Socialists and Anarchists is nothing but the label. Even in 1877, Anarchy and Socialism were identical. Albert Parsons, publisher of the Alarm, moved effortlessly between Socialism and Anarchy.

This is also the part that covers the rise of Socialism in the USA, in 1877, with the Bohemian pied pipers from what is now the Czech Republic. (Just 23 years later, Yellow Socialism, aka, National Socialism, would emerge from the same area). It mentions how members left the Socialist Labor Party and joined the International Working People's Association. Without any fanfare, PBS casually mentions that the IWPA is an "Anarchist" organization, without noting that the big difference between the Socialists and Anarchists is nothing but the label. Even in 1877, Anarchy and Socialism were identical. Albert Parsons, publisher of the Alarm, moved effortlessly between Socialism and Anarchy.The beginnings of the Red/Black Alliance (or Black/Red, if you like) -

On Thanksgiving Day 1884 the anarchists unveiled their new symbol. The black flag of hunger and death joined the red flag of social change.

On Thanksgiving Day 1884 the anarchists unveiled their new symbol. The black flag of hunger and death joined the red flag of social change.

Narrator: The Sunday picnics that Chicago's Germans enjoyed became more than picnics. They were a chance to spread the word and recruit. One Sunday, anarchist leader Samuel Fielden spoke of the wonders of a new invention, dynamite, which, he said, "science has placed within the reach of the oppressed." On Thanksgiving Day 1884 the anarchists unveiled their new symbol. The black flag of hunger and death joined the red flag of social change. Playing the anthem of the French revolution, the Marseillaise, they began a march which took them past Potter Palmer's elegant hotel, the Palmer House. Then on to the Prairie Avenue mansions of the capitalists who had "deprived them," their leaflets said, "of every blessing during the past year." "Every worker, every tramp must be on hand to express their thanks in a befitting manner."

Miller: They're marching down Prairie Avenue, okay, the very citadel of capitalism. And it's hard to march on a plant, but they're right at the homes of the capitalists. Never happened anywhere else like that. They collect what they call hoboes but they're anarchists as well. And they're going up and they're ringing the doorbells. And of course nobody's answering the doors. But they're screaming that they want bread or power. There'd just never been a direct demonstration quite like that.

Narrator: Albert Parsons read from the Epistle of St. James: "Your riches are corrupted...Your gold and silver is cankered, and the rust shall eat your flesh as it were fire...We do not intend to leave this matter for the Lord," he concluded. "We intend to do something for ourselves."

Narrator: They approached the Prairie Avenue mansion of Marshall Field, whom Parsons had attacked for discriminating against immigrant women shopping in his store. "Our international movement is to unite all countries and do away with the robber class," Samuel Fielden told the marchers. "Prepare for the inevitable conflict."They marched on the Prairie Avenue mansion of George Pullman.

Adelman: George Pullman was absolutely horrified with the sight of poor people walking up his street and ringing his doorbell. The next day he went to his attorney, Wert Dexter, and he said, "I want you to get this guy Parsons."

Schneirov: They were Catholic, they didn't speak English, they spoke German, they drank beer on Sundays, they went to saloons on Sundays. They were a threat. They were totally alien to this American, Protestant way of life.

Narrator: They marched on the Board of Trade when it opened an elaborate new building on LaSalle Street the next year. "The Board of Thieves", they bellowed, stood for "starvation of the masses, privileges and luxury for the few." One in the crowd yelled, "Blow it up with dynamite." To Chicago's business leaders these were not idle threats.

Miller: They're reading in newspapers about assassinations abroad. There're people being killed in Europe, including Czar Alexander at this time. The movement is extremely strong in Germany And now their speakers are coming from Germany to agitate. So they know the anarchists are serious.

Narrator: "The better classes are tired of the insane howlings of the lowest strata," warned General Phil Sheridan, "and they mean to stop them." On May 1st 1886, the anarchists did something unusual. They teamed up with the main stream labor movement - disgruntled railroad workers, packinghouse butchers, Bohemian socialists. Albert and Lucy Parsons led 80,000 workers down Michigan Avenue as part of a nationwide strike for labor's big issue, an eight-hour day. With its Mayor Carter Harrison supporting it, Chicago became the center of the strike.

Pacyga: "Eight hours a day for work; eight hours a day to sleep; eight hours a day to play in a free Americ-kay."

Schneirov: The anarchists didn't lead the eight-hour movement, but they attempted to commandeer it. August Spies, felt strongly that this was a demand that was, in effect, a revolutionary demand, even though it didn't openly say so. It was a demand that could not be won under the existent circumstances, and it was a demand that would inevitably lead the eight-hour movement into a revolutionary situation, under the leadership of the anarchists.

Miller: They told capitalists, Your function in life is to die. We're going to get you. We're going to bomb your factories. We're going to tear apart your system. The general strike's going to bring down capitalism. You'll be shot afterwards.

Pacyga: The streetcar lines are shut down. The city is shut down. This is a general strike. And there's tremendous amount of tension. Workers, of course, were winning, you know, the eight-hour day in the packinghouses.

Narrator: Workers struck the packinghouses on May 2nd. The packers, Chicago's largest employers, conceded to an eight-hour day - the same pay for eight hours that workers had gotten for ten. What happened May 3 at the McCormick Reaper Works got the anarchists involved in another labor dispute and ignited the most sensational labor incident of the 19th century. Cyrus Hall McCormick, the Reaper King, had died in 1884. A floral reaper adorned his casket. His last words were "work, work, work." His son mechanized the plant. Blades that used to be forged by hand were now forged by steam hammer. This threatened the skilled iron workers. In May 1886 they had been on strike for months. McCormick hired scabs to take their place.

Schneirov: The McCormick strike was over a long-standing dispute that had begun before the 8 hour day had begun, that turned on the attempt of McCormick to mechanize the whole process of iron molding and thereby to get rid of one of the strongest unionized forces, the iron molders union. And these were largely Irish. And so there was a very bitter struggle that was going on at that time. Some of the Bohemian lumber shovers and other socialists and anarchists had gone up there in solidarity with the McCormick workers. August Spies had made a very militant speech.

Narrator: When the whistle blew to end the shift on May 3rd, locked out strikers attacked the scabs as they left the plant. Police rushed in to protect the scabs. They killed two of the striking workers.

Adelman: Spies witnessed this, from behind a boxcar. He saw it. And he ran back to his office on Wells Street and he wrote a protest, and he left it on the desk and said, I want this circulated the next morning. And he told them to put a banner on it. Well, to his great dismay the banner that somebody put on it was "revenge", which was the last thing that should have been put on it. Because he didn't mean it to be that kind of thing.

Narrator: A second circular called for a rally the next evening at Haymarket Square. Haymarket Square was an open air market by day. By nightfall on May 4th, the pushcarts were gone. Chicago's popular mayor, Carter Harrison, was there and made certain the crowd saw him. It would ensure order.

Pacyga: It was a very peaceful rally. The anarchists were saying things that they always said. Death to the owner class, revolution. Mayor Harrison rode up and everybody yelled, "Hoosah, hoosah, Mayor Harrison." You know, and he took his hat off and he waved at the people and said his little campaign thing. And he stayed at the back and then the police captain, Captain Bonfield, came up, said, "What should we do with this rabble, sir?" And he said, basically, "Let them speak. They've said many worse things than they're saying tonight. And there's no one here. And he says, "I'm going to go home," and he goes home.

Narrator: Captain Bonfield dismissed most of his men. Not all. The last speaker, Samuel Fielden, remembered the men shot at the McCormick Works: "The law is framed for...your enslavers.," he said. "Throttle it, kill it...do everything you can...to impede its progress." Bonfield considered this inflammatory. He ordered the police to march. Fielden was winding down. "He that has to obey the will of another is a slave. Can we do anything except by the strong arm of resistance? ...War has been declared on us. People have been shot. Defend yourselves!" No one noticed the man lurking in the shadows. "Any animal will resist when stepped upon. Are men less than snails or worms?" In the name of the state of Illinois, I command you to disperse," the police captain said. "But we are peaceable," Fielden protested.

Narrator: Seven policemen were killed, mostly by friendly fire. The Chicago Times called the workers "rag-tag and bobtail cutthroats of Beelzebub from the Rhine, the Danube, the Vistula, and the Elbe." Labor's largest paper called them "wild beasts." The respected Albany Law Review called them "long-haired, wild-eyed, bad smelling, atheistic, reckless foreign wretches."

So, there you have it (and there is more in the documentary), a bunch of Anarchists, indistinguishable from Socialists, attacked innocent workers as they left the McCormick plant. The police were protecting victims under attack and some violent attackers were killed. Somehow over history, and a bit in this documentary, this has been twisted by the Leftists as some heroic stand for the Labor Movement. In reality, it was a bunch of thankless children in adult bodies who fell for the nonsense that fair wages were not enough and they deserved a business that they never invested a dime in. The Albany Review was down right prophetic in describing the later rally attendees as "long-haired, wild-eyed, bad smelling, atheistic, reckless foreign wretches," since nothing about their appearance or manner has changed in over one century.

Update: In a probably unwitting attempt at freshness and uniqueness, the funky, smelly #Occupy crowd plan to replicate the Prairie Avenue incidents mentioned above, this time in the Chicago suburbs, as reported by Roe Conn and Richard Roeper on WLS 890 AM, Chicago. Targets include towns where "high profile members of the 1% live" Check for updates on their blog.

Something very disappointing about this post is how hard it was to find the PBS information, vs. a CSPAN clip. PBS does not have the video online, one must order a DVD. If it were on any CSPAN channel, it would be free to view and share. Finding the transcript was easy, if you knew of its existence in advance. Trying to find it through the events mentioned is fruitless. Hopefully, this humble blog post will help others find this hidden gem for their research.

No comments:

Post a Comment